Economics and UX Strategy have more in common than either field would like to admit. Both claim to serve people; but both often end up serving the numbers instead. When a government celebrates quarterly GDP growth while its citizens ration heating and shrink their grocery lists, it feels eerily familiar to anyone who’s seen a company trumpet “record engagement” while its users quietly churn. The interface looks good — the experience, not so much.

Politics, like product design, has become a performance of progress. Ministers and spokespeople obsess over dashboards and KPIs, talking in percentages and baselines as though empathy were a rounding error. “Economic growth” becomes the North Star metric, worshipped without context, endlessly optimised but rarely interrogated. The copywriting is impeccable; the usability is appalling.

To me, the Budget is not politics — it’s interface design. It’s a glossy release note from a government treating the electorate as an audience rather than a user base. Each chart and soundbite is a UI element in a much larger design system that no one seems to be testing. And yet, like a product team in denial, they keep pushing updates that make the experience worse.

This is where UX Strategy can offer something useful — not to fix policy, but to decode its dysfunction. When you view democracy as a design system, the same principles apply: usability, empathy, accessibility, feedback loops. If those principles are ignored, trust decays and the system breaks. Which raises the question: if democracy is a design system, who’s doing the user testing?

Scenario: The Budget vs the Thermostat

Situation

Commentators circle the upcoming Budget like it’s a product launch — leaks, rumours, pre-briefs, spin. Each morning, the headlines hum with familiar optimism: inflation easing, GDP growth outpacing expectations, “stability returning.”

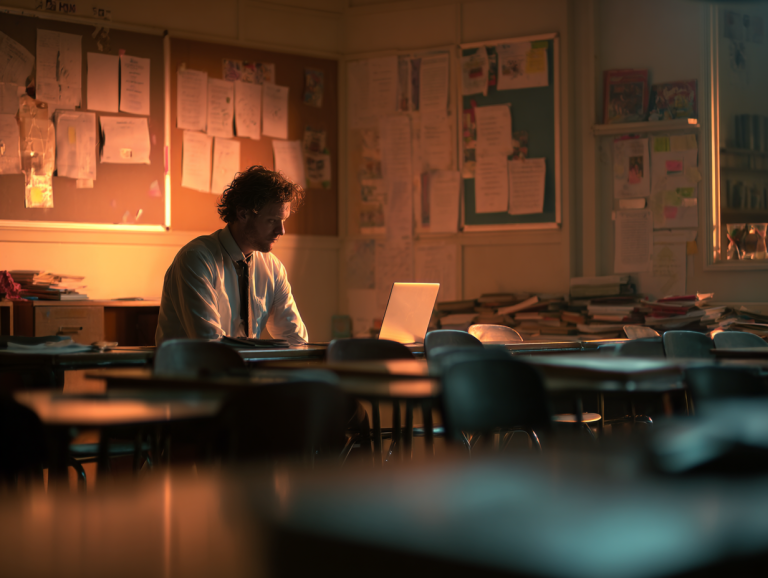

At his desk, a once-busy product professional scrolls through job listings and cost-of-living graphs with the same detached precision he once reserved for user analytics.

He’s become the user now — navigating a system that doesn’t seem designed for people like him.

Impact

The data is everywhere, but it feels increasingly abstract.

Bills climb faster than hope; the pound buys less each week. He notices how political interviews mirror stakeholder meetings — everyone fluent in metrics, no one close to the experience. The Chancellor talks of fiscal responsibility while energy companies post record profits.

He glances at the thermostat. Off, as usual. A second jumper will do.

Tension

He wants to believe that competence still counts, that somewhere in the noise someone is iterating toward something better. But every talking head sounds like a PM (Product Manager) celebrating vanity metrics.

GDP, growth, employment — all green on the dashboard, all red in reality. He recognises the pattern instantly:

Targets replacing purpose. Optics over empathy.

Approach

He keeps half an ear on the radio while tightening the language on his latest job application. The UX strategist in him can’t help mentally running a heuristic evaluation of government communication — inconsistent messaging, inaccessible jargon, zero feedback loop.

Every ministerial soundbite could be a tooltip written by ChatGPT. He wonders if democracy has become just another interface, optimised for persuasion instead of usability.

Resolution

He closes his laptop and looks at the blank wall opposite, as though waiting for a retrospective that will never come. In another month, they’ll announce the Budget and call it a plan.

For now he smiles without humour, and puts another jumper on.

Budgets and product launches share the same choreography: a polished reveal, a confident voiceover, and a deck of performance metrics that promise progress. Yet behind both lies the same fundamental flaw — a belief that storytelling can compensate for design debt. In government, as in product strategy, the copy becomes the interface, and the interface becomes the illusion.

What follows isn’t a political critique so much as a usability audit of power — an exploration of how language, metrics, and oversight have drifted from their original purpose. Because when democracy forgets its users, what’s left is a dashboard of slogans and a public left tapping the screen, wondering why nothing works.

The Frame of Reality

Politics has become a masterclass in interface design — not the functional kind, but the performative kind. Every press briefing, campaign slogan, and policy headline is crafted like a UX artefact, optimised for attention rather than understanding. The phrases are elegant; the flows are frictionless. But when clarity is replaced by persuasion, language stops serving people and starts serving power.

“Economic growth” might be the most successful piece of political UX copy ever written. It feels unassailable — simple, positive, future-facing. Growth equals good. Yet, like a deceptive “Continue” button on a dark-patterned website, it hides what comes next: who benefits, who pays, and what’s left out of view. The word does its job too well — it converts scepticism into compliance.

This is what happens when storytelling drifts from sense-making to stage-making. The government’s annual Budget announcement becomes an onboarding flow for the nation — rich in metaphors and animation, light on meaning. In UX terms, it’s the classic trap described in The Experience Economy: when emotion becomes the commodity, experience becomes performance.

The Budget, like any overproduced launch, prioritises applause metrics over usability. The interface dazzles, but the logic collapses. In UX, we call that a usability failure. In politics, they think that’s leadership.

The Drivers of Behaviour

If “growth” is the story, GDP is the scoreboard. It’s the ultimate vanity metric — a single composite number that claims to represent national wellbeing while saying nothing about lived experience. In UX terms, it’s the dashboard view: clean, confident, and catastrophically misleading. Like any product team chasing engagement stats, governments obsess over the visible uptick while ignoring the silent churn.

This is the political embodiment of Goodhart’s Law. Once a measure becomes the goal, it stops measuring anything useful. GDP was meant to describe economic activity; it now dictates policy, headlines, and even morality. When growth becomes a virtue in itself, everything else — equity, dignity, sustainability — is treated as a feature request for a future release that never ships.

The Budget’s glossy graphs are the perfect UI for this distortion. Up and to the right equals success; context equals clutter. But metrics don’t feel the cold. Metrics don’t skip meals. The obsession with numerical validation has created a democracy optimised for dashboards — a system where the appearance of progress is the product. If GDP were a UX metric, any designer worth their salt would flag it as a data integrity issue. Yet in the political design system, it’s still the hero metric.

The Mechanics of Accountability

In healthy systems, feedback keeps things honest. Products evolve because users can report friction. Designers test, iterate, and adapt. But democracy’s feedback loop is broken — the channels that should connect experience to action have become performance stages of their own. Oversight has turned into theatre; transparency into choreography.

Journalists quote numbers, not people. Watchdogs issue reports few will read. Public consultations are little more than checkbox UX — the illusion of interaction, not its substance. It’s all signal management, no signal processing. The state talks about “listening to hard-working families” as though it were a beta test, but the release notes never change.

In UX we talk about user testing as a safeguard against hubris — a chance to see how design holds up in the wild. In government, it’s the same principle applied at scale: a society’s usability test. Yet the test results keep coming back unread. The public speaks through protests, petitions, or simple disengagement — all forms of qualitative feedback. The system’s response? More metrics. More dashboards. More noise.

The principle isn’t new; it’s the foundation of User-Centred Design vs Business KPIs. When the success of a system is measured by what’s easy to count rather than what’s meaningful to experience, feedback becomes ornamental. A functional democracy would close that loop — treating civic frustration as design input, not dissent. Until then, we remain trapped in a dark pattern of governance: when outcomes disappoint, change the messaging, not the mechanism.

Conclusion

The Budget will arrive, the charts will rise, and the story will repeat. There will be talk of resilience, competitiveness, and growth — words chosen not to inform but to reassure. They’ll be tested for rhythm, not readability. Yet behind the choreography, the same interface remains: a government optimising for dashboards instead of dignity.

UX Strategy teaches us that every system has a user, and every experience has a cost. When policy is designed without empathy, that cost is simply passed downstream — into colder rooms, longer queues, thinner patience. The citizen becomes the unacknowledged QA tester of a product that was never truly built for them.

If democracy really is a design system, it needs a redesign — one that values usability over spectacle, clarity over spin, and feedback over façade. Because systems that refuse to listen don’t stay broken; they erode. And when the next Budget arrives wrapped in another perfect slide deck, perhaps we’ll remember that progress measured in numbers alone is just a story with the users left out.

Relational Observations

Metrics that inspire trust

-

Trust is built on traceability.

When citizens can see how data connects to decisions, numbers regain credibility. -

Empathy is the missing data point.

Dashboards without human context turn insight into indifference. -

Transparency is a usability feature.

Policies explained in plain language are easier to trust — and harder to weaponise. -

Accountability scales through feedback.

Listening loops convert frustration into design intelligence, not political risk. -

Meaning beats metrics.

Growth without dignity is just aesthetic success — a smooth UI for a failing system. -

Iteration restores integrity.

When governments adapt like good product teams, public faith becomes the retention metric.