It’s finally happening — my ADHD assessment is booked. After years on the waiting list, I thought I’d feel relief. Instead, I feel anxious. Not about what I might be told, but about what that knowledge might do to me.

When I first mentioned ADHD to my GP over two years ago, he looked up from the screen and asked a question that has stayed with me ever since: “Why do you want to be assessed?”

At the time, I didn’t know how to answer. I still don’t.

I’m not chasing validation or an excuse. I don’t want a label or a shortcut. I’ve already learned how to survive — and even succeed — without a formal diagnosis. Years of self-engineering have turned necessity into method: structure, iteration, humour, grit. It’s what people call “high-functioning,” though I’ve never been comfortable with the term. To me, it just means I’ve built a working system on top of unstable code.

And yet, the closer the assessment gets, the more I wonder what the price of clarity might be. I’ve spent so long reverse-engineering my own brain that the idea of someone else writing the manual feels invasive. This, I suppose, is my field report from the edge of clarity — part curiosity, part caution, all lived experience.

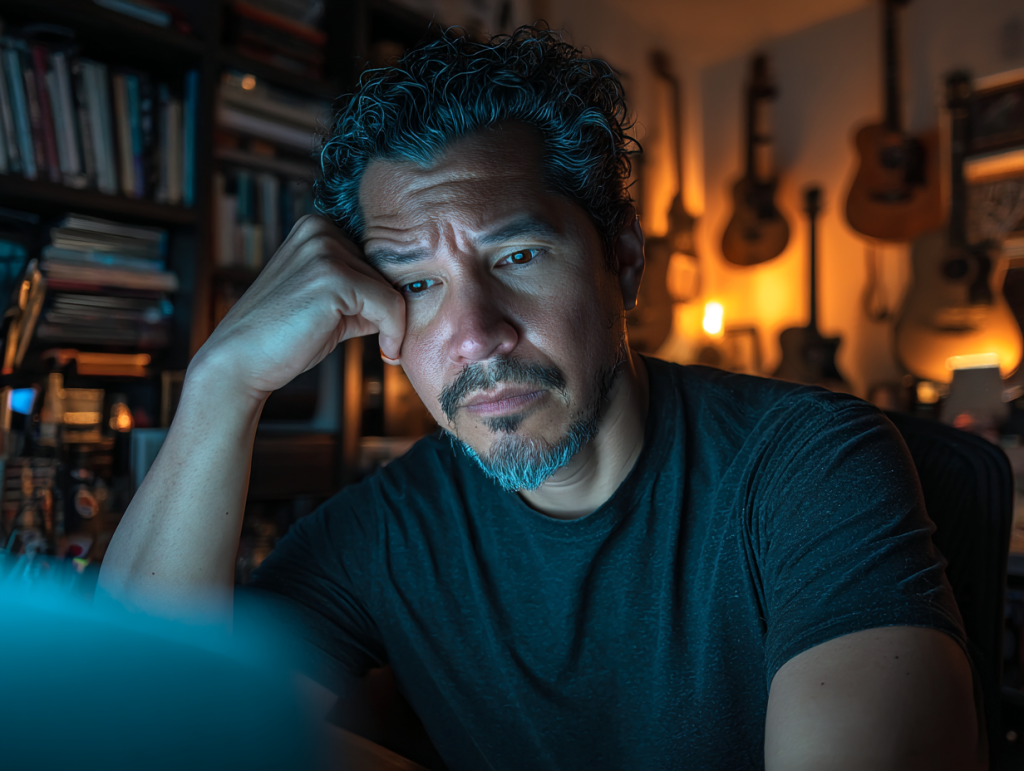

Scenario: Checkbox Moment (inner monologue)

Situation

Mid-career. Capable. High-functioning by design, not by default. Every scaffold — every list, every loop, every morning reset — the quiet architecture of survival.

The routine isn’t discipline; it’s defence. I’ve built my own operating system one coping mechanism at a time, patching over memory leaks and distraction crashes.

And then I reach the end of an application form.

Impact

The usual question: “Do you have a disability or medical condition (including ADHD or neurodivergence)?”

Underneath it, the third option — polite, neutral, supposedly safe: “Prefer not to answer.”

I stare at it longer than I should. Even the glow of my monitor feels like it’s judging me.

Tension

Tick “yes,” and I invite scrutiny. Tick “no,” and I erase what feels like a big part of myself.

“Prefer not to answer” — does that look evasive? Defensive? Dishonest? Is there an algorithm somewhere flagging the choice as “inconclusive” or “indecisive.”

I start to imagine a recruiter wondering what’s being hidden. I start writing imaginary emails justifying the decision I haven’t even made.

Approach

As usual, I logic my way out. I remind myself that I’ve built systems that work — systems no diagnosis could design better. I’m more than functional; I’m thriving.

Resolution

And now, I’m finally booked in for an assessment – great news, right? Maybe — finally — an assessment could bring me understanding.

But the loop won’t stop. Now I’m consumed with the thought that an answer could undo years of quiet engineering. Or expose the architecture as overcompensation.

Medication might sharpen my focus, or it could sand down the very edges that make me quick, creative, alive.

What if the fix breaks the very thing that works?

That’s the paradox I keep circling: I’ve built a life that works, and yet I’m terrified someone else might try to fix it. The assessment feels like progress, but it also feels like interference — an audit of a system I designed under pressure and somehow kept running.

I know this much: my version of “functioning” didn’t come from medication or manuals. It came from building workarounds faster than the world could build obstacles. Maybe that’s why I’m nervous. Because high-functioning isn’t the absence of struggle — it’s the constant act of engineering through it.

High-Functioning Isn’t Hiding — It’s Engineering

For years I thought I was masking, performing competence so the cracks wouldn’t show. But when I look closer, I realise I wasn’t concealing anything — I was designing. Every list, every colour-coded calendar, every morning reset wasn’t an act of camouflage; it was infrastructure. I’ve been running continuous integration on my own brain: prototype, test, patch, redeploy.

People see the output — the delivery, the composure, the reliability — and assume ease. They don’t see the version control underneath it all: the dozens of micro-adjustments that keep me aligned. High-functioning sounds flattering, but it’s really just a synonym for always debugging.

I’ve learned that consistency doesn’t come from impulse suppression; it comes from building rails sturdy enough for chaos to travel safely. That’s not denial — it’s design. And maybe that’s what I’m most protective of. Because while a diagnosis might explain why I operate this way, it won’t change how I built it. This system is mine — and it works.

The Bureaucracy of Belonging

The irony of the diagnosis process is that it’s designed to validate difference but delivered through standardisation. You spend your life learning to operate outside the lines, and then you’re invited to prove it by colouring within them.

Every question, every checklist, every neat little scale feels like a bureaucracy of belonging — a system asking you to make your edges legible so it can confirm they exist.

I’ve learned to speak fluent compliance when I have to. It’s a survival dialect: answer in the right tone, give examples, show awareness. But each time I do, a small part of me wonders whether I’m authenticating myself or auditioning.

- I want understanding, not accreditation.

- I want someone to see the architecture, not just tick off its features.

Maybe that’s the real tension: institutions need proof, but I already have performance. My evidence is lived — the routines, the achievements, the late-night recoveries.

I don’t need a certificate to belong to myself. If the system catches up one day, great. Until then, I’ll keep submitting results instead of forms.

The Interface of Overthinking

Digital life was meant to make things easier, but for me it’s just made overthinking more efficient.

Every platform has its own polite way of asking who I am: dropdowns, declarations, “optional” disclosures.

Each time I’m confronted with a box about health, neurodiversity, or “reasonable adjustments,” I feel the same quiet surge of panic — as if honesty requires a user manual.

I know the logic behind it: inclusion, representation, equality.

But from this side of the interface, it feels less like empathy and more like exposure.

Algorithms can’t process context; they only process input.

So, I hover. I reread. I imagine the data trails.

I wonder whether my hesitation has already been logged somewhere, interpreted as indecision, unreliability, risk.

It’s absurd, I know.

But this is what a high-functioning mind does: it doesn’t just overanalyse; it renders the overanalysis in high definition.

Even “Prefer not to answer” becomes a thought experiment in optics and probability.

And the irony is that all this reflection, all this careful self-management, is the very thing the question is trying to account for — yet the system will never see it.

To the form, I’m a checkbox. To myself, I’m a living debug session.

Building Clarity from the Inside Out

Whatever happens next, I know one thing for sure: I already have a system that works.

It isn’t elegant, but it’s mine — a patchwork of habits and heuristics that turns distraction into motion and chaos into flow. I built it piece by piece, not from diagnosis, but from necessity. If clarity comes, it will have to coexist with that design, not overwrite it.

People talk about ADHD management as if it’s a product you can subscribe to — medication, coaching, methodology. But the truth is, the scaffolding has to start from within. No one can outsource your rhythm.

If the pills help, they’ll enhance a structure I’ve already built, not replace it. If they don’t, I’ll keep iterating — the way I always have — until friction becomes function again.

Maybe that’s the quiet advantage of being high-functioning: you learn early that no one’s coming to rescue you. You design your own rescue instead.

So, while the system might still be deciding what to call me, I already know what I am — a builder of clarity in a world that keeps trying to sell it back to me.

Conclusion

So here I am — still waiting, still building. The assessment is on the horizon; Schrödinger’s Diagnosis: until then, I both have ADHD and I don’t.

I still have no idea how to answer the question on the application form, and maybe that’s where the truth sits: somewhere between indecision and intention. If a diagnosis comes, I’ll take it for what it is — information, not instruction. I won’t hand over the operating system I’ve spent years refining. I’ll listen, learn, adjust if I must, but the architecture stays mine.

Because clarity was never something the system could grant me. I earned it the slow way — through design, through iteration, through the quiet engineering of a mind that refuses to stand still.

And if that’s not progress, I don’t know what is.

Tactical Takeaways

The Fear Behind the Label

- Progress isn’t permission.Keep building your own system, even when others try to define what working looks like.

- High-functioning isn’t hiding.It’s the architecture of survival — invisible, precise, and yours by design.

- Diagnosis explains; it doesn’t author.Use information, but don’t surrender authorship of your narrative.

- Systems need maintenance, not rescue.Your routines are evidence of competence, not symptoms to cure.

- Disclosure is optional; authenticity isn’t.Protect your agency when sharing your story in professional spaces.

- Clarity is iterative.You’ve been earning it all along — this is simply the next version.