Productivity is often sold as the art of doing more, faster. But for most professionals, the real battle isn’t speed — it’s duplication. Hours evaporate not in grand strategy meetings or carefully chosen priorities, but in the tedious loops of rework: copying figures into yet another spreadsheet, re-explaining the same problem on the phone, re-formatting documents so they look the part.

These loops masquerade as diligence. They even win praise from managers who applaud responsiveness and thoroughness. But they are, in truth, a tax — invisible on the balance sheet but paid daily in time, energy, and morale. And like any tax, the more hidden it is, the more corrosive it becomes.

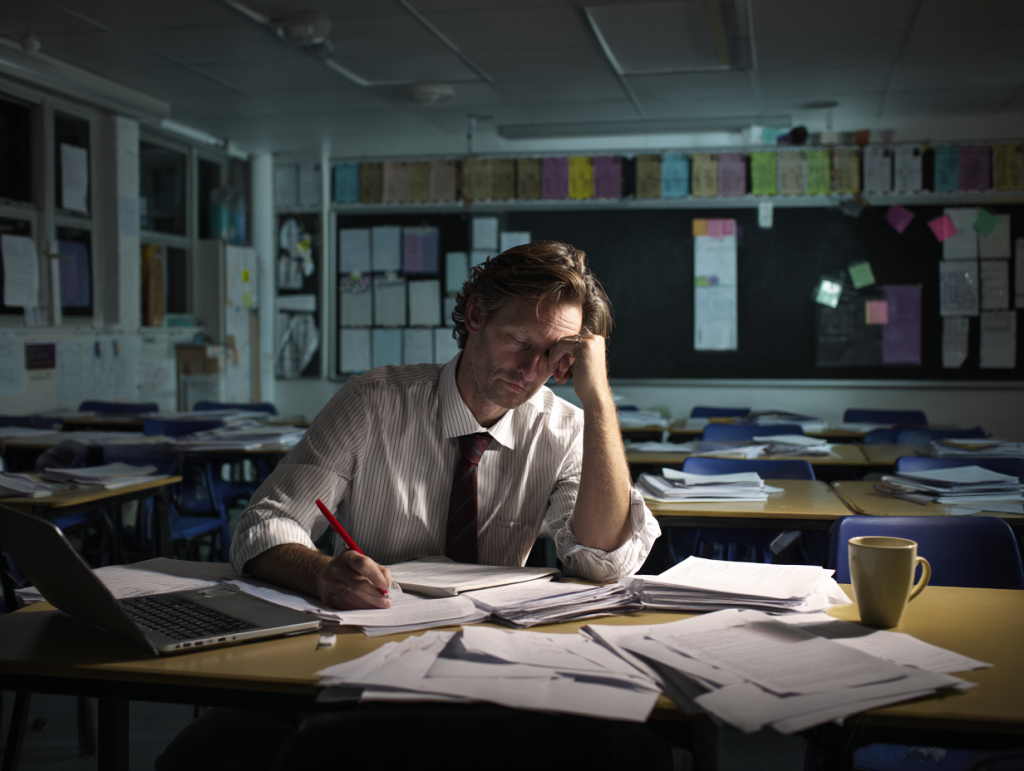

Scenario: The Overextended Teacher

Situation

A teacher stays late after a full day of lessons. The classroom is quiet, but their desk is buried under printouts, spreadsheets, and reports that all say the same thing in slightly different ways.

Impact

Instead of preparing tomorrow’s lessons or marking students’ work, they spend hours re-entering and re-formatting results. The effort doesn’t improve outcomes — it just reshapes the same data into the formats leadership want to see.

Tension

The teacher knows this duplication adds no value, but resisting the requests risks being seen as uncooperative. Each new cycle of admin leaves them more depleted, less present for students, and increasingly cynical about the system.

Approach

Leadership praise the stack of reports as evidence of diligence. No one questions whether the process itself is broken. The duplication continues, normalised as part of the job.

Resolution

By the time the reports are submitted, the teacher is drained. What looks like rigour from above feels like futility on the ground. Productivity has been swallowed by duplication, leaving less energy for the work that actually matters.

The Admin Gap

Duplication often begins in the shadows of administration. When information is incomplete or entered manually, the cracks are inevitable: missing records, delayed updates, avoidable errors. What should be a straight line of workflow becomes a scavenger hunt, with professionals burning hours piecing together fragments of the truth.

For the teacher, this means chasing down which students are actually sitting an exam, or double-checking whether marks have been uploaded correctly. For others, it might mean reconciling conflicting spreadsheets, or spending half a morning tracking down a missing purchase order. The work that should be the work gets displaced by detective work.

These admin gaps rarely feel dramatic in the moment. Each extra call, each missing line of data, seems trivial. But cumulatively, they siphon energy and focus away from the real purpose of the role. Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints makes the point neatly: the bottleneck doesn’t just slow things down, it dictates the pace of the entire system. Here, the bottleneck is clarity. Until the missing information is filled, nothing moves forward.

The emotional toll is subtle but corrosive. Professionals adapt with weary resignation: “If I don’t check it, no one will.” But in doing so, they absorb the hidden tax of duplication. Productivity debt accrues invisibly, as hours meant for teaching, problem-solving, or creating are spent patching the cracks of a leaky admin layer.

The Feature Gap

Sometimes the bottleneck isn’t human error — it’s the tool itself. When software lacks basic functionality, or when its features are buried and unknown, professionals are left doing work that machines should handle in seconds. Exporting data becomes copying it line by line. Sharing analysis means screenshots pasted into Word documents. The tool may be modern, even expensive, but it quietly converts skilled professionals into clerks.

This gap is rarely visible to leadership. They see a subscription invoice, not the lost hours on the ground. But to the people using the tool every day, the gap is glaring. They know the data could be automated, integrated, or at least exported cleanly — yet instead they wrestle with manual repetition. The frustration is not just the wasted time, but the insult of being forced into tasks that add no value.

The Technology Acceptance Model explains why this happens. Tools only drive efficiency when their features are perceived as useful and easy to use. When staff aren’t trained, or when core functions are absent, adoption collapses into workarounds. At the same time, Brynjolfsson’s “Productivity Paradox” reminds us that IT investment doesn’t guarantee results. In fact, when poorly implemented, it can amplify dysfunction by formalising waste at scale.

The result is a cruel irony: the very systems purchased to boost productivity end up sapping it. Professionals comply, but with resentment. Each duplicated task is a reminder that the gap isn’t in their diligence, but in the design choices that shape their tools.

The Relational Gap

Not all duplication is accidental. Often, it’s demanded from above. Leaders ask for data in a particular format — not because it adds clarity, but because it suits their habits or optics. Teachers repackage results into spreadsheets or Word docs even when systems already contain the data. In offices, employees spend evenings crafting slide decks summarising dashboards that already exist. The work is duplicated not for outcomes, but for appearances.

This is the heart of the relational gap: power dynamics that prioritise optics over efficiency. To the individual, it feels like punishment. Time and energy are sacrificed for rituals that look rigorous from above but feel futile on the ground. Resentment doesn’t come from the work itself, but from the knowledge that it changes nothing.

Goodhart’s Law captures the problem perfectly: when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. Once leadership fixates on specific outputs — another spreadsheet, another report — the activity becomes self-serving. Rigour is measured by the volume of duplicated work, not by its contribution to outcomes.

The Phoenix Project makes the same observation in a different arena: firefighting often masquerades as progress. IT teams in the novel rush to close tickets, but in doing so, they reinforce a cycle of duplication instead of addressing root causes. The optics of responsiveness are rewarded, while the system quietly deteriorates.

The alternative is captured in Greg McKeown’s Essentialism: focus on what matters most. True productivity isn’t about multiplying outputs, it’s about stripping away the redundant. Yet in many institutions, the relational gap ensures the opposite — duplication is normalised, even celebrated, while genuine clarity goes missing.

Conclusion

Duplication is the most invisible of thieves. It doesn’t announce itself with missed deadlines or budget overruns — it quietly drains hours, erodes energy, and corrodes morale. From the outside, it looks like diligence. From the inside, it feels like futility.

But frustration alone won’t shift the system. To change the pattern, we have to dissect it. Was the wasted effort caused by an admin gap, where information was missing or delayed? A feature gap, where tools lacked the functions to match the task? Or a relational gap, where leadership demanded outputs that served optics, not outcomes? Each one is a different problem, requiring a different conversation.

The real danger is treating duplication as normal — part of the job, a cost of doing business, the price of compliance. It isn’t. It’s a hidden tax that compounds until good people burn out and good work gets buried. Productivity isn’t about hacks or hustle; it’s about clarity. Do the work once, and let it stand. Work twice, and you’re not progressing — you’re circling the drain.

Relational Observations

Duplication in Disguise

-

Admin gaps create invisible bottlenecks

Professionals burn hours patching incomplete or delayed information. -

Feature gaps force manual workarounds

When tools lack core functionality, users become clerks for the system. -

Relational gaps prioritise optics over outcomes

Leadership demands outputs that look rigorous but add no value. -

Duplication is mistaken for diligence

Extra reports and reworked data are praised while real productivity erodes. -

Frustration corrodes engagement

Time wasted on loops drains morale and undermines quality of work. -

Clarity is the antidote

True productivity comes from isolating each gap, challenging it, and refusing to work twice.