Everyday tools shape how we work. We rely on them without question — until the cracks show. And when they do, something strange happens: instead of demanding better, we adapt. The dysfunction becomes part of the background noise of professional life.

This is the quiet crisis in user experience. It’s not the spectacular product failures that sink companies. It’s the steady drip of features that don’t serve us, the basic functions that never quite work, and the creeping normalisation of poor design.

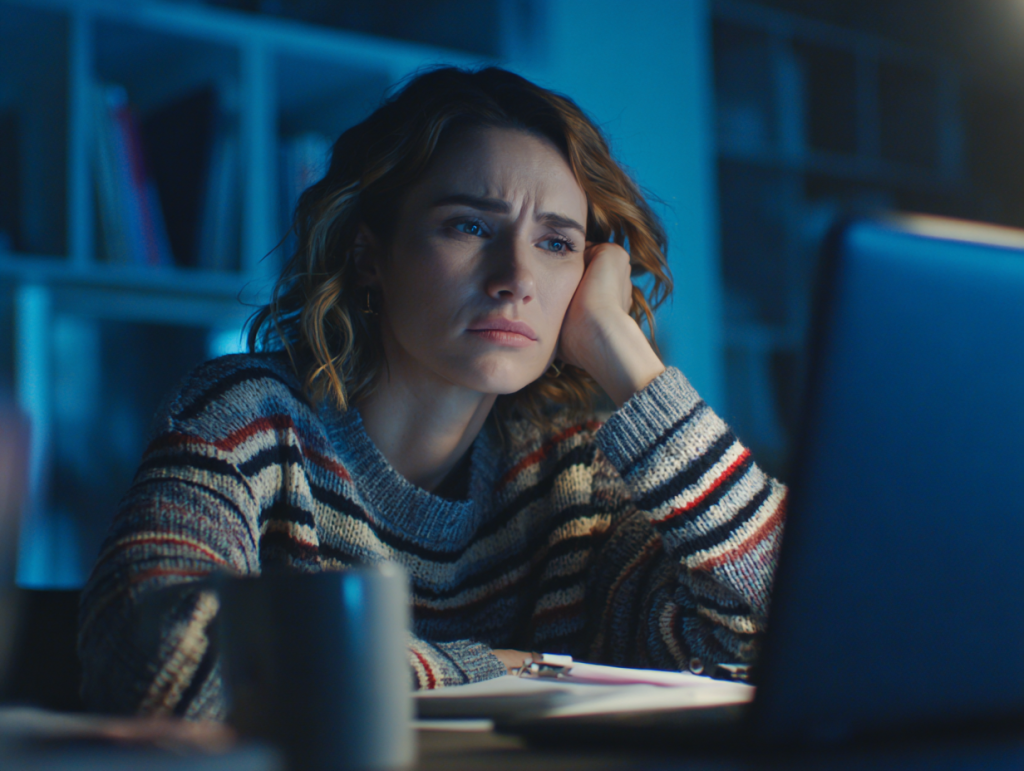

Scenario: The Search That Never Works

Situation

You need to find a critical email in Outlook — a contract detail, a project approval, a date.

Impact

You type in the keywords. Nothing useful appears. You add filters, change sort orders, try again. Still nothing. Minutes tick away while you dig through folders manually. Stress mounts, deadlines loom.

Task

You just want a simple thing: to find the email you know exists.

Actions

Instead of fixing this core pain, Microsoft launches more integrations, more add-ons, more AI assistants. Features nobody asked for, while the basics remain unreliable.

Results

You adapt. You build shadow workflows — manual folders, starred items, saved PDFs. You stop trusting the search function completely. Outlook’s shortcomings become normalised, baked into the professional experience of millions.

Normalised dysfunction in everyday UX

Outlook search is not unique. It’s just a vivid reminder of how quickly dysfunction becomes accepted. We work around the cracks: manual processes, endless patience, muted expectations.

This is the adaptation trap. We stop being surprised when things don’t work as they should. A broken form field? We refresh the page. A pop-up nobody asked for? We click “close” without thinking. A clumsy update? We sigh and move on. Each compromise lowers the baseline, until even the most basic functionality feels like a luxury.

The danger isn’t just wasted time — it’s eroded trust. When users stop expecting better, organisations stop striving for it.

A diagnostic lens for dysfunction

What if we could actually score these shortcomings? Not just complain, but measure the gap between optics and outcomes. Imagine a simple lens that gives weight to three things:

- How much a feature looks good on the surface

- How much substance it actually delivers

- How well it translates real user needs into outcomes

Through that kind of lens, Outlook search would score high on optics — polished UI, new integrations, AI on the horizon — and painfully low on substance. The core need remains unmet.

Framing dysfunction this way makes the problem visible. It stops being just another annoyance and becomes something you can diagnose, track, and hold accountable.

From annoyance to systemic diagnosis

Why do these gaps persist? Because organisations are often rewarded for optics. Shipping a new feature or shiny integration looks good in a press release. It demos well on stage. But if it doesn’t address real user needs, it’s just noise.

This is how dysfunction becomes systemic. Incentives skew towards what’s easy to announce rather than what’s hard but valuable. Teams fall in love with their own ideas. Leaders chase short-term wins. And somewhere along the way, the user’s voice is drowned out.

The lesson for UX strategy is clear: success isn’t measured in the volume of features, but in the alignment between needs and outcomes. When we fail to listen — or when we choose optics over substance — we invite dysfunction to become the norm.

Conclusion

Outlook’s broken search is more than a quirk. It’s a case study in how easily we normalise dysfunction. Millions of professionals live with it every day; not because it’s acceptable, but because they’ve stopped expecting better.

That’s the quiet crisis in UX. Not spectacular collapse, but slow erosion. Not idiocy, but misalignment. Not outrage, but resignation.

The first step to breaking the cycle is to notice it — to name the gaps between promise and reality, between optics and outcomes. Once we see dysfunction clearly, we can start designing for clarity instead of compromise.

Because users don’t need another feature banner or shiny integration. They just need the basics to work — and to work well.

Behavioural Principles

Normalised Dysfunction: The Quiet Crisis in UX

- We adapt to broken toolsWorkarounds become habits, even when they waste time

- Silence lowers expectationsFrustrations go unvoiced, and dysfunction is accepted as normal

- Optics distract from outcomesShiny features often win over fixing core pain points

- Incentives drive misalignmentOrganisations reward what looks good, not what works well

- Erosion is invisibleDysfunction creeps in gradually, unnoticed until trust is gone

- Clarity must be intentionalRecognising and naming gaps is the first step to change