Digital transformation promises clarity, but too often delivers confusion. The language is polished — integration, automation, efficiency — yet the lived experience tells another story. Inside the organisation, progress rarely feels like progress.

While customers see the visible interfaces of change, the people behind them wrestle with the hidden ones: systems that don’t talk, workflows that contradict, and dashboards that shine while confidence quietly erodes. Internal users adapt, workaround, and patch — until transformation becomes a performance rather than a practice.

What happens when we apply UX Strategy to the machinery of transformation itself? By treating Product Information and Lifecycle systems as experiences to be designed, not infrastructures to be maintained, the experience of work improves, and so does the credibility of the progress it produces.

Scenario: The Data That Everyone Trusted — Until They Didn’t

Situation

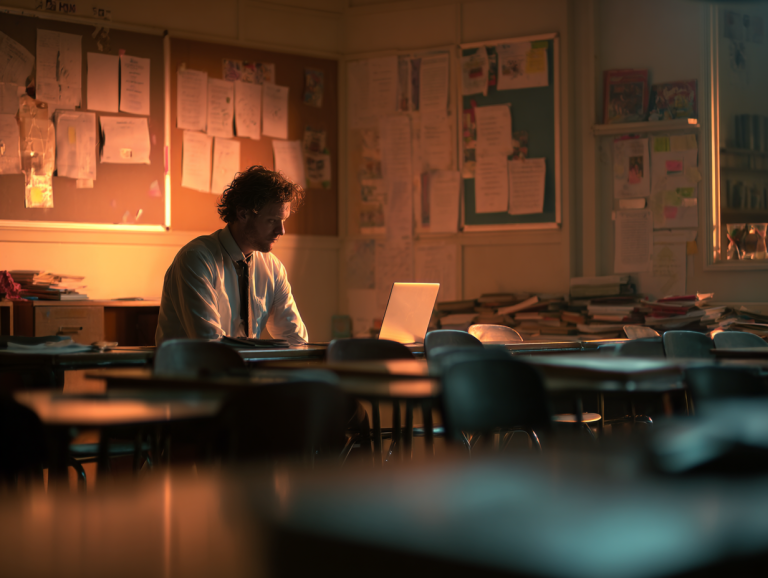

A content manager in a large retail organisation has just started using the company’s brand-new product information platform — the flagship outcome of a much-publicised digital transformation.

On paper, it’s everything the business needed: faster workflows, unified data, fewer manual steps. But within days, the reality feels less like an upgrade and more like a reshuffle.

Impact

Fields have moved. Shortcuts no longer work. The familiar rhythm of getting products live has been replaced by a maze of new validation rules.

Every small friction ripples outward. Tasks take longer. Deadlines tighten. Confidence dips. The new platform was meant to simplify, yet somehow the process feels heavier.

Tension

Teams don’t reject the change out of resistance — they’re simply exhausted by the constant need to relearn. The system may be smarter, but no one feels smarter using it.

Approach

Instead of complaining, the team starts documenting what actually happens between the buttons and the brief.

The screenshots, the retraced steps, the quiet Slack messages asking “Does this look right?” — all of it paints a clear picture: the issue isn’t functionality, it’s empathy.

The system was designed for data flow, not human flow.

Resolution

When release deadlines begin to collide with the platform’s friction, pragmatism takes over. Managers and content teams start building their own parallel paths — exporting data, keeping private sheets for quick edits, passing product updates through chat threads instead of the official workflow.

Everyone knows it’s not ideal, so they handle the workarounds quietly, limiting how far they spread. But even with care, the drift is inevitable. Each off-system tweak, each unsynced file, reintroduces the inconsistencies the transformation was meant to eradicate.

What happened here isn’t rare — it’s routine.

Transformation projects collapse into workaround culture not because people resist change, but because oversight mistakes compliance for confidence. When progress is measured by output instead of trust, it’s only a matter of time before teams start optimising for survival.

That’s where the real dysfunction begins.

When Oversight Turns Into Theatre

The first thing to break in a transformation isn’t process — it’s confidence.

When internal systems begin to drift, leaders reach for visibility: dashboards, governance decks, RAG statuses. Yet somewhere between transparency and truth, a subtle inversion occurs — the rituals of oversight replace the reality they were meant to protect.

Progress starts being performed rather than proven.

This drift isn’t unique to technology. Sociologists studying high-reliability organisations warned that teams under pressure often normalise small deviations until failure becomes invisible. In digital programmes, the same pattern plays out through dashboards that always look green. It feels responsible — diligent, data-led — but when measurement becomes theatre, the audience starts believing its own script.

The irony is that these systems are often built with the best intentions: feedback loops, quality gates, sign-offs. But oversight without empathy only measures motion, not meaning. Double-loop learning — the practice of questioning the governing logic behind a metric — rarely survives an executive timeline. Instead, we optimise for the evidence of diligence. Governance becomes a choreography of reassurance.

The UX of oversight is belief. If the people closest to the work can’t feel seen, the fidelity of feedback collapses. What looks like control from above feels like surveillance below — and once that trust breaks, no amount of reporting can hold the system together.

When the Numbers Start Making the Rules

Once confidence cracks, measurement rushes in to fill the void.

The instinct is rational: if belief wavers, count harder. But inside a transformation, that reflex often reverses cause and effect — progress starts serving the metric instead of the mission. What began as evidence becomes the agenda.

It’s a quiet version of Goodhart’s Law: when a measure becomes a target, meaning becomes the casualty.

Dashboards reward what can be captured (volume of records processed, velocity of releases, error-rate deltas) while the subtler indicators of success (like clarity, comprehension, and shared confidence) stay unmeasured and therefore invisible. Over time, teams start optimising for what shows up on slides. The system looks efficient precisely because it has stopped telling the truth.

Behavioural economics calls this incentive distortion: people do what is rewarded, not necessarily what is valuable. In UX terms, the metric becomes a dark-pattern interface — nudging behaviour toward compliance rather than improvement. The more the organisation tracks completion, the less space it leaves for reflection.

A tactical UX approach reframes metrics as part of the experience, not the evidence of it. Instead of asking “How much did we ship?”, the better question is “What did our users stop needing to ask?” When measurement shifts from volume to validity, numbers regain their purpose — they start describing reality instead of defending it.

When the Tool Outruns the Team

Most transformations fail not because the technology is wrong, but because it arrives faster than the culture built to receive it. New systems land like foreign objects — sleek, logical, and emotionally inert. They meet rituals, habits, and workarounds that evolved under a different gravity. The software may be the upgrade, but the people are the operating system.

Sociotechnical theory described this decades ago: every tool embeds a set of assumptions about how humans should behave around it. When those assumptions collide with existing practice, friction is inevitable. Teams adapt, of course — but they do so through coping strategies, not cultural alignment. In practice, adoption looks less like onboarding and more like negotiation.

This negotiation rarely happens in daylight. It plays out in whispered guidance, Slack shortcuts, annotated screenshots — the shadow UX of survival. These are the artefacts of decision fatigue: users trying to reconcile yesterday’s confidence with today’s confusion. It’s what Diffusion of Innovations would call the “implementation gap” — that murky middle where enthusiasm fades and real work begins.

Treating adoption as a design challenge reframes transformation from delivery to enablement. The goal isn’t to make people fit the system; it’s to make the system feel inhabitable. Culture doesn’t need to catch up to technology — it needs to recognise itself inside it. Only then does the tool become an ally rather than an intrusion.

When Progress Finally Feels Like Value

Every transformation carries an implicit promise: the effort will be worth it. But when the daily experience of using the system feels harder than the one it replaced, that promise starts to decay. Progress becomes a transaction — users invest attention, patience, and time, but the return arrives in dashboards rather than relief.

Value, in this context, is experiential. It’s not what the organisation gains; it’s what its people stop losing. A stable system saves cognitive energy. A clear interface restores rhythm. A transparent workflow gives time back to teams who’ve been operating in fog. This reciprocity is the essence of UX Strategy — designing exchanges where clarity feels like reward.

Organisational theorists call this the psychological contract: the unspoken agreement between individuals and institutions about what each owes the other. When that contract is honoured, engagement compounds; when it’s broken, even small frustrations feel like betrayal. Every click, delay, or error becomes a micro-withdrawal of trust.

The tactical opportunity is to make that contract visible. Design governance like a service, not a gate. Reward comprehension as much as completion. When users sense that their effort translates into collective clarity, the system starts giving back. Progress becomes something people want to sustain — not because they’re told to, but because it finally feels fair.

Conclusion

Digital transformation isn’t a technology problem — it’s a trust problem.

Every system, no matter how advanced, inherits the empathy of the people who built it. When that empathy is missing, dysfunction doesn’t explode; it seeps — through dashboards, metrics, and rituals that confuse accountability with assurance.

Treating progress as a product means designing it the same way we’d design any user experience: start with understanding, prototype for clarity, iterate for belief. The transformation succeeds not when the system launches, but when its users no longer need to defend their trust in it.

The internal user experience is the true frontier of change.

It decides whether innovation scales or stalls, whether progress feels genuine or performative. The technology will keep evolving — faster, smarter, more connected — but without empathy at its core, it will always outpace the humans it was built to serve.

Progress that endures doesn’t demand confidence; it earns it.

And when we design for that — when we make the experience of work as coherent as the systems that support it — transformation finally lives up to its name.

Tactical Takeaways

Designing Progress That Feels Real

-

Measure belief, not just delivery.

Dashboards can show completion; only users can confirm confidence. -

Make oversight feel human.

Governance should signal reassurance, not surveillance. -

Reward comprehension, not compliance.

Velocity means little if nobody understands the system that created it. -

Treat adoption as a design phase.

Implementation is done when people stop compensating for it. -

Design governance like a service.

Support teams with clarity loops, not control gates. -

Balance effort with clarity.

Every extra click, delay, or error withdraws trust; design to repay it.